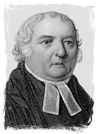

Samuel Marsden was born July 28th, 1764, at Horsforth, near Leeds, His parents were Methodists, of the "good, old fashioned Methodism" type. His father was a blacksmith, and in the forge, no doubt, he and his sturdy little son had many a heart-to-heart talk, even under the sound of the rhymic blows of the hammer, and with sparks flying round. Many a strip of metal was cut and heated to white heat, and deftly shaped as the little lad watched. Meanwhile God Himself was fashioning an instrument to be used in a far country, for at a very early age Samuel Marsden showed great ability, and wished to become a minister. It was no passing phase.

Samuel Marsden was born July 28th, 1764, at Horsforth, near Leeds, His parents were Methodists, of the "good, old fashioned Methodism" type. His father was a blacksmith, and in the forge, no doubt, he and his sturdy little son had many a heart-to-heart talk, even under the sound of the rhymic blows of the hammer, and with sparks flying round. Many a strip of metal was cut and heated to white heat, and deftly shaped as the little lad watched. Meanwhile God Himself was fashioning an instrument to be used in a far country, for at a very early age Samuel Marsden showed great ability, and wished to become a minister. It was no passing phase.

He was educated at Hull Free Grammar School, and afterwards selected on account of his gifts to go to St. John's College, Cambridge for that purpose. There he showed his firmness of principle and his courage, and the sincerity of his faith in the Lord Jesus Christ as his Saviour, from which sprang his desire to take the Gospel to the heathen.

Australia and New Zealand were the places to which his mind turned with special longing, and when, through the influence of Chas. Simeon, of Cambridge, and Wm. Wilberforce, the champion of slaves, he was appointed second chaplain to "His Majesty's territory of New South Wales," he was overcome with a deep and solemn joy, accepting the post "if no more proper person could be found." Before sailing, he married Miss Elizabeth Tristan, who was a devoted helpmeet for 42 years.

The ship in which they sailed was in command of a captain who knew not God, save by the use of His Name in oaths, and officers and crew were of the same stamp. It is not hard to imagine what this meant to the missionary, especially as he would be nine months on the voyage. In vain he begged the captain to allow him to preach to the ship's company, but, with God, even the wrath of man is made to praise Him. And thus it was in this case. England and France were at war at this time, and ships voyaged in company guarded by a battle ship. After three months at sea the captain of Marsden's ship invited the captains of the other three ships of the company to dine with him, the second Sunday in October. Marsden took the opportunity of speaking to one of them about preaching, and the promise was given to speak to Marsden's captain. He did so and a service was held that evening. Marsden preached on John 3:14, 15, from the quarter deck to a very attentive audience. During the remainder of the voyage he had ample opportunity of declaring the whole council of God, and he certainly used it, though it appears, he was not permitted to see any good results. But who can tell? The day shall declare it! Long ere this Marsden may have found fruit of which he little dreamed.

On March 2nd, 1794, they landed in Australia. Their quarters were in the barracks of Paramatta, near Port Jackson. In this convict settlement when a man had obtained a ticket of leave he would settle down to fast money-making, his heart unchanged; the same with those whom later he was able to employ—master and man both of the criminal class. A difficult field for Marsden; and when to his duties as a chaplain were added those of a magistrate it became more difficult than ever. The men who should have supported and helped him in his ministrations, resented his integrity and worked him much harm.

He lost his first two boys through accidents, sorrows which he endured "with calm and even dignified submission"—this man "who said little, though he felt much."

His mind was ever on the alert to see where God's servants were needed, and it was he who wrote to the L.M.S. about Tahiti, to which island, in 1817, they sent John Williams. And, too, his heart turned longingly to New Zealand, 1200 miles E.S.E. of where he was stationed. It seems incredible that Maoris should cross that wide stretch of sea to visit the white settlement, but Miss Marsden says her father sometimes had 30 Maoris staying at his parsonage. Very welcome he made them, and learnt from them much about their country and its needs.

In this way he actually began his missionary work in New Zealand at the distance of 1200 miles, ere ever he had set foot on her shores.

In 1807 he returned to England on the aged merchant ship "Buffalo," which nearly sunk on the way. During his stay of two years he urged the C.M.S. to take up the cause of New Zealand, suggesting the civilising of the natives, and following up with the Gospel, a policy which he saw afterwards was wrong. In later years he said: "You will find civilisation follows Christianity more easily than Christianity follows civilisation." The C.M.S. saw this from the first. In exhorting William Hall and John King, who went forth to the cannibal Maoris, they said: "Do not mistake civilisation for conversion, . . . and while you rejoice in communicating every other good, think little or nothing done, till you see those who were dead in trespasses and sins quickened together with Christ."

Marsden returned to Sydney in 1809. On the ship in which he sailed he rescued a Maori chief, Duaterra, from destitution, took him to his home for six months, and when Duaterra returned to his country, he prepared the way for the missionary's reception.

In 1814, Marsden purchased the "Active," and sailed for the Islands on Nov. 19th. The party landed whilst a tribal war was in progress, but so great was the influence of Marsden that he and his friend Nicholas were able to go unarmed to the camps, and to bring the dispute to a happy ending.

On Sunday, with the Union Jack floating in the breeze, Samuel Marsden set up the Gospel Banner in the Name of his God. He said: "I felt my very soul melt within me when I viewed my congregation, and considered the state they were in." To one of his hearers, an old man, tottering on the brink of the grave, the message was indeed glad tidings. Rangi, his name, a chief, and formerly a great warrior. "When I think of Heaven and of Jesus Christ I am glad, because when I die I shall leave this flesh and these bones here, and my soul will go to Heaven." His last words were: "My heart feels full of light."

Marsden and his friends were able to hold services in the open air without fear, though they were surrounded by Maoris, each with spear ready to hand, and another weapon, "pattoo-pattoo," on their person. And so mightily did the Gospel prevail that some laid the spear aside for the sword of the Spirit, instructing others in the blessed truths which had made their own souls free.

Samuel Marsden had to return to Sydney, where many troubles awaited him, and where slanders against him were rife. In this dark time he had encouraging letters from Charles Simeon, William Wilberforce, and Elizabeth Fry, and was enabled to return to New Zealand several times, making a stay of 8 or 10 months on each occasion. Again and again he acted the part of peacemaker between warring chiefs, and prevented much bloodshed. The natives had great love and respect for him, calling him "the friend of the Maoris."

Once he visited the Wesleyan Mission Station, Wangaroa, and finding Mr. and Mrs. Leigh ill, took them on board to convey them to Port Jackson. They were wrecked but no lives lost, for they all reached an island in the ship's boat. The natives did all possible for them, so greatly did they revere Samuel Marsden.

In 1830 he made his sixth visit, when the tribes were all at war after the death of Hongi. There was a big council, a very stormy time it was, but at last the great chief cut a stick into pieces as a sign that his wrath was broken and pacified.

In 1835 Samuel Marsden lost his beloved wife. He himself was nearly 70, and his work was well nigh finished. On the occasion of his last visit to New Zealand he was carried in a chair to the place of meeting. One old Maori chief sat and looked into his face for hours. When reproved, he said, "Let me alone. I shall not see him again." Then came farewells, for the ship was standing off the shore. As they sailed away in the moon-light, he spoke of his wife and the Heavenly Shore. Someone said he would soon see her. "God grant it," said he. Again in Sydney, he kept open house for young New Zealanders, enjoying their happiness as they came and went.

Then came the end, following on a cold contracted during a 25-mile ride in his gig. He had intervals of consciousness, and in the last they spoke to him of the good hope in Christ. "Yes, that hope is indeed precious to me now—precious—precious!" And with that word on his lips he passed into the Presence of Him, whom having not seen, he loved.

From Twelve Mighty Missionaries by E. E. Enock. London: Pickering & Inglis, [1936?].

>> More Samuel Marsden